Sustainability analysis of Road Construction Projects

Transport infrastructures, including roads, are increasingly being upgraded to accommodate more traffic, increase the level of service, provide mass mobility, reduce vehicle operating cost and create development opportunities in Kigali City. Policies and plans have been put in place to ensure effective feasibility of road projects, however, there has been lack of consensus on a methodology to guarantee sustainability upon assessment and analysis during road pavement design, construction and maintenance.

Sustainable construction is one of many subsets of sustainable development and refers to the creation of construction maintenance, operation of infrastructures, buildings and roads which helps to shape communities in a way that sustains the environment, bring into existence long term durability and overall, enhances the quality of life (Winter, 2008). On the other hand, one of the greatest challenges facing humanity in the twenty-first century is our ability to reconcile the capacity of natural systems to support continued improvement in human welfare around the globe (Miller, 2011).

The Rwanda Transport Policy is aligned with its 2020 Millennium Vision which, inter alia, provides for modern transport infrastructure and cost effective and quality services with due regard to safety and environmental concerns. Considering that, infrastructure should be developed in a sustainable manner to support economic growth of the country, mobility of the population and serve as a “pivot” for exchange of goods and services at national and regional level (MININFRA,2012).

Despite the current approaches to integrating the social, economic and environmental feasibility of pavement projects including road infrastructures, there has recently been a lack of consensus on a methodology to guarantee sustainability upon assessment and analysis during highway pavement design, construction and maintenance in Kigali City. As new roads are constructed and old roads upgraded, the need to satisfy lifecycle functional requirements of social development, environmental sustainability and economic growth of roads is consequently unsatisfied.

According to Jamilus (2013), construction industry is one of the most significant industries that contribute toward socio-economic growth especially to developing countries where Rwanda belongs. Nevertheless, Ismail (2013) appraises the nature of the industry as fragmented, unique and complex to face chronic problems like time overrun (70% of projects), cost overrun (average 14% of contract cost), and waste generation (approximately 10% of material cost).

Rwandan architects and construction industry have been urged to design and build green and sustainable structures in order to help the country achieve its vision of becoming a green and climate resilient country by 2050 (REMA, 2016). The call was made during the launch of Rwanda Green Building Organization RWAGBO, which was established as part of Rwanda’s pursuit of a green growth approach to economic development favouring the development of sustainable cities and villages. The organization is to supplement the role of Rwanda Building Code and National Housing Policy adopted in 2015, as well as the 2011 National Green Growth and Climate Resilience Strategy.

Since the report published by Brundtland Commission (1987), sustainable development has become a matter of prime importance for all development activities and in 2015, the report of World Bank “Improving environmental sustainability in road projects” has discussed that embedding sustainability principles and best practices into road projects in low- and middle-income countries is a challenge for several reasons, including changing or varying degrees of commitment and limited financial resources. In addition, there is often a lack of understanding about sustainability concepts and how to address them, given country and project specific characteristics (Montgomery et al., 2015).

Not withholding the fact of development, according to Reid et al,. (2008) road maintenance and new construction have a direct effect on these priority areas:

- They consume large quantities of construction materials and generate large quantities of waste.

- The extraction, processing and transporting of these materials is a significant source of greenhouse gas emissions, particularly in the production of cement and asphalt.

- Use of primary aggregates in preference to recycled or secondary aggregates results in depletion of irreplaceable natural resources and damage to the environment where the aggregates are located.

- Incorrect use of materials can result in pollution of the environment.

Some findings on the Remera-Rwandex Road

The explored literature gave insights to the researchers to carry out site visits on different spots and occasions; developing their statements on sustainability for the current context. The case study for precise data collection was a 4-lane highway, linking the main spine of Kigali road network, from Remera to Rwandex. Data identification was done by using the rating system’s categories, primary data was acquired using interviews and questionnaires while secondary data was collected through publicly available reports and shared reports with the construction project teams.

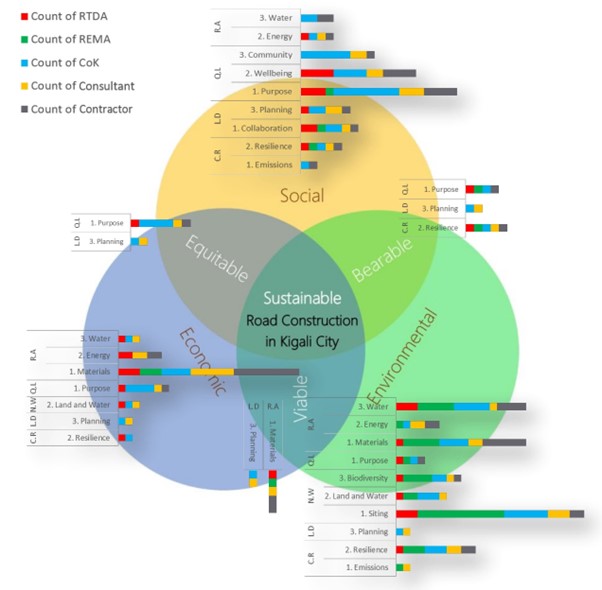

Stakeholders’ Triple Bottom Line (TBL) analysis

The three-sphere framework was initially proposed by the economist René Passet in 1979 and for this study to analyse each stakeholders relationship to economical, social and environmental aspects of the project as for sustainability; each question of the 144 questions in its categories was scored weighed: 1 for ‘not related’, 2 for ‘partially related’ and 3 for ‘absolutely related’. The graph illustrates and clearly shows the influence and what would be the participation of every stakeholder in specific categories and subcategories that contextualize the project from planning to implementation in all evaluated credits. This in contrast can relatively be applicable to other urban road construction projects with consideration of new consultants, contractors and project executive bodies.

In Rwanda, specific bodies parenting from ministries such as the Ministry of Infrastructure (MININFRA), Ministry of Environment (MoE) and the Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning (MINECOFIN) plays a major role in every road project. Channelling responsibilities downwards, it goes straight to the Rwanda Transportation Development Authority (RTDA) which mainly oversees transport infrastructures in the whole country; the City of Kigali (CoK) monitors projects of a reasonable scale within urban boundaries. In case of any major project the government through its institutions issues bids and contracts to consultants and then to contractors to implement the project; CoK in this case is responsible.

Rwanda Environmental Management Authority (REMA) comes in to regulate, inspect and monitor all environmentally sensitive aspects of major construction projects. It applies its authority to the extent of discontinuing activities which are non environmentally compliant. It follows up to make sure that measures of mitigation in the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) of the project are followed and implemented. To evaluate each stakeholders input for sustainable construction requires relative attention on the methodology of project delivery, nature of contracts and collaboration between project team members.

Concluding thoughts

All stakeholders in road construction as analyzed earlier should be brought to more awareness on sustainable construction as specific as it would apply to their duties. Together with that, we would like to advocate for “Sustainability Analysis” through ‘rating’ or early ‘assessments’ in project planning stage to be a pre-requisite for project implementation with accreditation of internationally renowned rating systems. Once more, for incorporating the sustainability concept in the construction sector for Rwanda we may see that making sustainable choices and new construction is not something that should be done in isolation or on an opportunistic basis. A framework of steps that can be domesticated for sustainable practice can be developed further; we might face some barriers technically or politically but with efforts and positive will altogether, shall hopefully gear the performance of sustainable road construction in Kigali City.

Many thanks to David Nkurunziza, Isaac Dusengimana and Gustave Mizero. Read the full article here